Coaching Techniques I learned from “the Major”

September 8, 2017

Civilian Marksmanship Program▸The First Shot▸Coaching Techniques I learned from “the Major”By Michele Makucevich

Michele wrote the following article as both a memoriam and a way of encapsulating some of the better coaching techniques she learned from Major Bill Barker, of Albuquerque, NM.

I was fortunate to have worked with the Major in running clinics, coach schools and matches for over a decade as well as to have called him my best friend.

In great works of literature and classic movies there are scenes that permeate the memory; moments of catharsis or deep emotion which have the power to move us, change us, mold or reflect us.

When I think of Major Barker, it’s a lot like that. With a flair for the dramatic, the timing of a great comedian and the wisdom of a sage, my recollections of the man so many referred to as “the Major” replay in Technicolor in my mind’s eye.

I met Major Barker about 15 years ago. Our junior teams were competing at Wolf Creek in Georgia. A couple things stood out; they were good shooters, and they knew how to have fun. I was a little more judgmental back then and my initial impression was that he needed to watch his shooters more closely. I had my athletes on a virtual lock down when they weren’t on the range. But what I saw as supervision, he saw as stifling the spirit and preventing growth. So, while his shooters were surfing hotel room stairs on ironing boards, mine were penned into their rooms, presumably getting their eight hours of pre-competition sleep. Both our teams were successful, but Barker’s teams had more colorful stories. They also produced adults of his own ilk – free-spirited, untamed, sometimes brash, but always confident. Many went on to academies (80+ at last count) and others enlisted. But, he’d be the first to tell you that he wasn’t recruiting – he was building good citizens. He didn’t judge others by his standards – he helped them form their own. While it is no wonder that a large number chose to follow his footsteps into the military, he was just as proud of the students who forged their own paths.

His confidence was apparent in all he did. When asked the salutary, “How are you today?” His response was generally, “Better than anybody.” Early on, I found this somewhat enigmatic. I asked for clarification. “What do you mean when you say that? Do you mean you feel good? You feel better than anyone else could? Or, do you mean, more egotistically, that you literally feel yourself to be BETTER than anybody?” In the way that only Major Barker could, his immediate, terse and still enigmatic response was, “Yes.” And with that “yes” came that smug, self-assured and simultaneously amused smile complimented by a twinkle of those blue eyes.

Confidence was something that Major Barker gave to others as well. His sometimes-harsh standards, which if administered by a lesser leader may have resulted in resentment, was, instead, demanded in such a way as to instill a sense of confidence in the recipient. He demanded because he believed, and that belief bolstered all those he had contact with into believing in themselves. Major Barker did not ask for the impossible, he demanded best efforts. A savvy coach, he knew that process leads to outcome, and while he made the one routine, he made the other possible.

Balancing his demands was compassion. And he had an abundance. With a sixth sense for the emotional tsunamis that were often hidden beneath the stoicism of adolescence, Major Barker had a knack for saying just the right thing at the right time. Whether it was a movie quote or one of his own “Barkerisms,” he walked the line of acknowledging challenges with neither maudlin emotion nor a diminishing paternalism. He was simply “there,” and that solidness leant strength. One of his favorite sayings was, “Unsolicited advice is criticism,” which was a quote he credited to one of his daughters. And he avoided that, offering, instead, a shoulder and an ear over as much time as was necessary.

A Marine through and through, Major Barker spent fifty years in uniform; 25 in the Corps and an additional 25 as a military science instructor and the head military instructor for the ABQ public schools. While most people are fortunate to have one successful career, he achieved two, successfully melding the passion and ideals of the Corps into his teaching career. It was a calling he embraced with enthusiasm that was matched only by the thousands of lives he touched.

A large part of his teaching was dedicated to marksmanship training and coaching. He viewed shooting as a vehicle for instilling lessons that would propel his students to success beyond the range. And as a coach, he was masterful, setting a bar few will ever match. I learned a lot from him that I have tried to incorporate into my own coaching.

Anyone who spent any time around Major Barker knows he was fond of stories to illustrate his points. He told them like PG-13 parables that would stick with the listener and come back in times of need. Sometimes these stories would undergo some modifications in the retelling, “It’s my story, and I’m sticking to it,” but they were always both entertaining and somehow instructive.

Here is my story of just a few of the things I learned from the Major; things that can strengthen any program and help mold another generation of “great Americans.”

Adult coaching may win individual matches, but peer coaching builds a dynasty.

During his tenure at La Cueva High School, Major Barker’s teams accrued near legendary success. He sent numerous athletes on to the American Legion National Championships, several winning the National title. In the National Junior Olympic Three-position Air Championships, his teams topped the podium year after year, even achieving an unprecedented double National team title in both sporter and precision the same year! One would assume that with such successes, he must have spent every minute on the line. But, he didn’t. He used his experienced athletes to mold the beginning shooters. He allowed those more experienced cadets to practice leadership and garner respect while simultaneously allowing the novices to identify role models and set goals. Believing that “we won’t get better until we all get better,” he used peer coaching to foster a sense of teamwork. But, such a philosophy demands a lot from a coach. It forces one to divest himself from the ego of indispensability. And this is the fulcrum of another lesson.

A coach is there to guide and support, not to think for the athlete or to use his team’s success as a trophy of his own.

Barker was not a “humble” man, but he was assured enough of who he was that he didn’t need external recognition. His self-evaluation was enough, and he easily credited others for success. “I’ve always been fortunate,” he’d say with a smile. And, it was that belief in his own fortune, his recognition of those good things that others may overlook, that made him such an optimist. He expected the best. He believed that the best was achievable, and his positivity was contagious. But, while expecting a good outcome, he prepared for that outcome. Part of that preparation was observation.

Learn from those who are most successful and emulate what makes them so.

Several years ago, during the National Coach Conference at the Olympic Training Center, the attending coaches were treated to a breakout session in which the most recent Olympians gave a Finals demonstration, followed by a Q&A session. A study in concentration, Major Barker could be seen evaluating each position and taking in every variation in pre-shot routines. When the time came for questions, he raised his hand and said to the bronze medalist, “I noticed you were chewing gum during the final. Do you always? Why?” The athlete responded that he felt more relaxed while chewing gum and didn’t get as nervous. Many of the coaches either shook their head in disagreement or simply laughed. Certainly, with an Olympic medal, the case could be made for gum chewing. Barker’s follow up question brought the house down. “What flavor?”

Major Barker was a student as much as a coach. He observed, he learned and he passed it on. He believed that competition is the greatest preparation for competition.

“Shooting for record is like getting a report card.” Athletes cannot be allowed to avoid being graded.

Recognizing that our sport is much less subjective than others, Barker prepared his athletes for competition by forcing them to shoot for score frequently and become comfortable with handling results. Though he separated process from outcome, he forced his charges to confront both. It was more than about launching lead, however, it was about deliberate and focused attention and repetition. “Practice doesn’t make perfect; PERFECT practice makes perfect.” Major Barker taught his students and athletes to strive for perfection, whether it be in presenting a perfect uniform or firing a perfect shot.

To achieve perfection, “all he wanted was a fair advantage.”

Achieving an advantage requires one to be a student of the game, and an integral part of that is to know the rules of the game.

When teaching the Level 1 Coach School, Major Barker would frequently appall his audience by declaring that his success was due to cheating. “If you ain’t cheatin’, you ain’t tryin’.” Having heard this several times, I would inwardly groan. But, it was effective. He had their attention. And then he explained. “If the rules allow two sweatshirts under your jacket then three would be even better, but since three is against the rules and two is allowed, why would you only use one?” Barker never cheated, but he examined the parameters of fair play and took advantage of every opportunity to gain what he called “a fair advantage.”

Know the strengths of your people and let them shine.

Not every athlete is destined for greatness. But Major Barker did not judge his students based solely on score. He found ways for all to contribute to the team. Maybe an athlete was a great student who could tutor a higher scoring individual or maybe she was highly organized or a great fundraiser. Valuing the individual strengths of team members leads to more balanced and happier teams. It recognizes individual strengths and builds character by teaching that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. And doing this re-emphasizes the importance of team. It always came back to that. Team. He taught independence through a recognition of dependence. Again, that sense of “we won’t get better until we all get better.”

We all got better from knowing the Major.

Among the litany of quotes he used, Yoda’s, “Do or do not. There is no try,” was a favorite.

Major Barker DID. He ran programs, raised funds, elevated psyches and acted as both rudder and anchor for those he led and cared for –a trying was not enough. He was mission oriented and all about team. And he made everyone around him feel that sense of belonging that leads to success.

As I think of the loss I feel, I can hear him in my head, “It is what it is, darlin’.” He meant this saying not as an excuse or cop out, but as a factual commentary that pushed one to move forward. “It is what it is” was a recognition that some things are beyond our control and a challenge to know that difference between the acceptance of what cannot be changed and the courage to find solutions for what could.

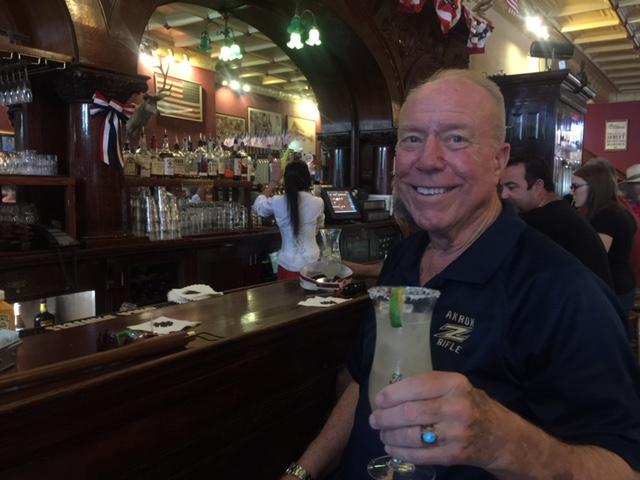

I know that the Major would not want any of us to “just stand there with our teeth in our mouths.” He would expect us to continue to practice perfectly, to see the world positively, to observe keenly and find a fair advantage. He’d want us to build a generation of confident and compassionate individuals who can lead our nation and to enjoy a good Bloody Mary on a Friday night, shared among friends.

While we all strive to contribute to this world and to make it better for our having been here, Major Barker touched an unfathomable number of lives and was, truly, “better than anybody.”

Major Barker was one of my mentors as a coach in this sport. He will be missed, but never forgotten. Great article.

I knew Bill for over 20 years, we lost a great American.