SNIPER VS. COMPETITIVE SHOOTER

March 6, 2015

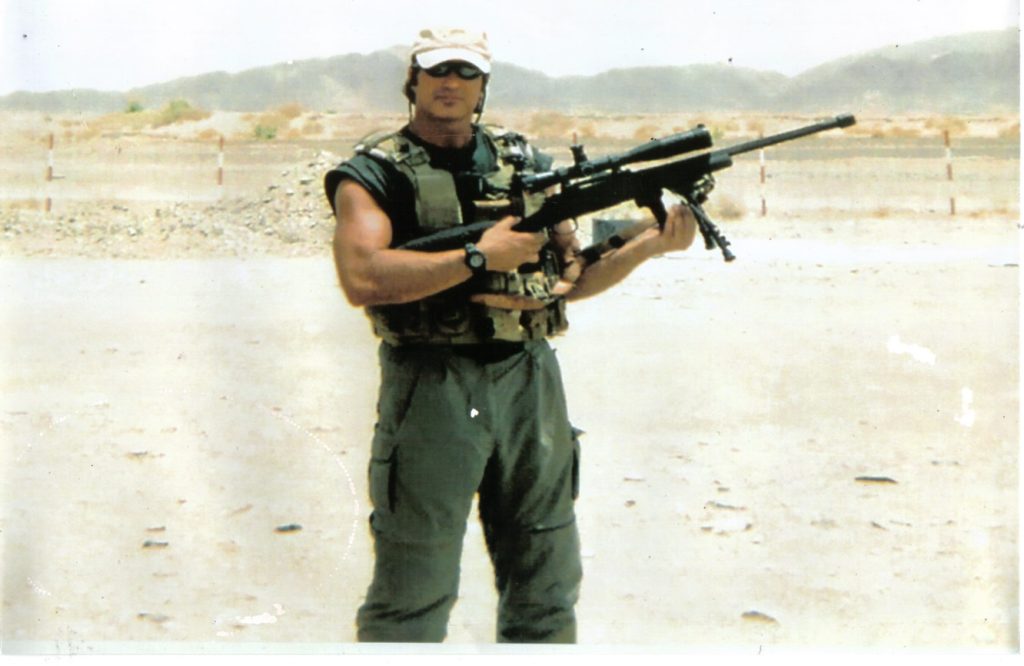

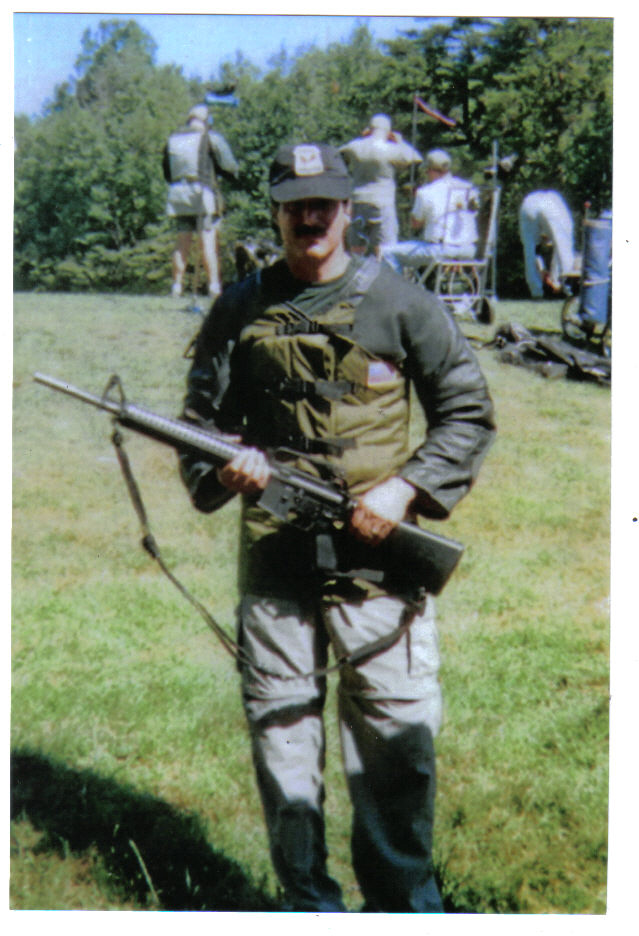

Civilian Marksmanship Program▸The First Shot▸SNIPER VS. COMPETITIVE SHOOTERSubmitted by Steve Sciarabba, Distinguished Rifleman/Presidents 100/M1 Carbine National Winner/US Army Sniper

Just within long-range high-power rifle shooting alone, there are all manners of classifications: 200 yards, 300 yards, 600 yards, cross-course, standing, sitting, prone, slow fire and rapid fire. To win, a shooter must excel in all these disciplines over days, often in varying conditions, including torrential rain and excessive heat, at distances that can be difficult to see and comprehend with the naked eye.

During the course of a match, the shooter must also physically haul his or her heavy rifle with ammunition and all equipment to the various distances – equipment which may include a range cart, spotting scope, shooting floor mat and, most importantly, a heavy shooters jacket that can compress and stabilize the body during the actual shot itself (which is put to the ultimate test every year in the Wimbledon Cup Long Range 1,000-yard High-Power Championship).

This may sound like a competition geared toward snipers, but one of the first things you learn upon delving into the world of shooting is not to confuse competitive marksmen with snipers. With the popularity of the book and movie “American Sniper,” and since I have lived in both worlds, I will share in the debate.

The way I see it is this:

In military terms, snipers infiltrate insurgent locales, negotiate a variety of terrain and, on occasion, take a shot. However this is only one element of their jobs, which also might include missions like scouting and reconnaissance, observation and security. A competitive marksman, however, trains year-round for competitive shooting yet doesn’t see combat action. Instead, he or she spends time competing at a series of events – improving his or her marksmanship skills.

As a result, each community sees the other with a certain amount of disdain; snipers view competitive marksmen as “paper punchers” (reference to paper targets), and competitive marksmen view snipers as less inept in the shooting skills. To sum it up, excellence in either discipline is defined as the ability to hit the target effectively.

“From my perspective the only difference between the sniper and the competitive marksman is simply this: In competition, it’s about winning; in sniping, it’s about surviving.”

Consider the rescue of Capt. Richard Phillips of the American cargo ship Maersk, Alabama. From 75 feet, three Navy SEAL Snipers picked off a trio of Somali pirates who were holding Phillips hostage in an 18-foot covered lifeboat. The operation required three shots, the difficulties of which were quite complex. The snipers had to use night-vision scopes and synchronize their shots from a swaying ship at a bobbing craft on the open sea. One of the targets was visible only through a window, and the pirates had AK-47’s to the captain’s head.

But the shots themselves: “I respect the conditions and the engagement, but really, for a Distinguished high-power rifle competitor like myself and others, that’s an easy shot – that was, what, 100 feet? With a rifle we start at 200 yards. For most of the competitive marksmanship community, that’s a shot that could have been taken with a handgun!”

As for the sniper viewpoint, retired Gunnery Sergeant Jack Coughlin, a legendary Marine Corp sniper in Vietnam who had more than 60 confirmed kills in combat, spoke for his compatriots on the subject of marksmen in his autobiography, “SHOOTER.”

“Paper targets don’t shoot back,” he wrote. “So that’s really kind of boring.”

By the end of the Vietnam War, however, top U.S. military snipers using converted commercial hunting rifles were able to pick off targets as far as 1,200 yards away. Now, with better technology in weapons systems and ammunition ballistics, snipers reliably can hit a human silhouette at a distance of upwards of a mile, and just a few years ago a British soldier named Craig Harrison set a distance record when he toppled two Taliban fighters from a staggering 2,500 yards.

Consider also that the average military sniper will be shooting at an E-type or IPSC silhouette target in training. A hit anywhere on steel is a hit – hit the target anywhere. Hear the “BONG” – done. In competition shooting, the defining difference is how close you can get all (or the majority) of your shots into a smaller, more precise objective 10- and X-ring.

At Sniper School, Qualification and Field Craft training teaches a soldier how to engage the threat and to survive it. Highpower competition teaches an individual how to shoot with precision, without the threat. Combine those two in the correct proportions and you have one formidable operator! It’s not an either/or, it’s a both – and the best can do both.

Carlos Hathcock was one of those rare individuals. He carved a niche in Marine Corp history for his legendary sniper missions, as well as becoming a nationally recognized shooting champion. Fifty years ago this summer, in 1965 as a Distinguished Rifleman, he won the Wimbledon Cup at Camp Perry. To be that effective both as a battlefield sniper and as a competitive marksman requires extraordinary qualities.

Being in both worlds, I can assure you military snipers use far more “tech” stuff than competitive shooters ever thought of using. A Data Book? A good sniper keeps these, too. Talk about milling a target to get the range and then failing to adjust for climate and weather conditions somewhere in austere third-world parts unknown countries!

“I’ve personally seen zeroes change rapidly by a full MOA and more during rain and sandstorms coming through – and the drop in the barometric pressure on scene. The range won’t change, but your POI (point of impact) sure as heck will.”

If you think this just applies to snipers, think again. Camp Perry in the rain, wind and humidity is very unforgiving, as well. Both a good sniper and a competitive shooter, however, will have data on this and will make the correct adjustments for it.

“Except the qualified Sniper School graduate who hasn’t been back on the range for anything other than his regular qualifications . . . probably won’t.”

As far as physical and mental attributes and characteristics, the fact is, I’ve never met a successful long-range shooter who wasn’t very intelligent in either a very analytical or an OCD-savant kind of way. And indeed the Army uses a psychological exam as part of the selection process as to what makes a good sniper school candidate and has found that the common personality type is having “meticulous attention to detail” and “overachievement tendencies.”

For a competitive marksman, however, if you wanted to become the kind of elite shooter who could be competitive at the level of the National Championships, then first and foremost you need to master the physical aspects of the sport. This means steadying and maintaining three different body positions (standing, sitting, prone) timed at three different distances. Plus, keeping the rifle snug against your shoulder to “eat the recoil” factors in to the physical aspects of static shooting, as well as the ability to control your breathing patterns or training your body to get “pumped down” rather than pumped up during high-pressure competitive situations.

Some are so adept at this that they can actually control their heartbeats – on a monitor there would be a slightly longer pause during the shot. For the sniper, it comes with not being as deliberate but perhaps more methodical and on-demand in many instances because of the sometimes unpredictable target environments and mundane over-watch missions in varying terrains.

In conclusion, I would like to point out that there is virtually no money in competition and no glory in being a sniper. Both get little-to-no media attention, and both are arduous and difficult to explain. So why do either?

If you ask both the competitive shooters and snipers, they’ll talk about an obsessive need to master the equipment and conquer the conditions – “the challenge of putting a bullet through a target time after time is still very amazing to me – the precision of the shot; that if you line up the sights real carefully, control your breathing and body real carefully, and squeeze the trigger real carefully, that bullet will go that whole distance and land in the middle of an object the size sometimes smaller than a dinner plate.”

Talk to the participants, and they’ll tell you the common denominator to both is the “shooting,” and to be chasing that lonely pursuit of perfection for either requires being the most prepared, the most proficient and the most persistent.

Help to hunting them down in a means thank you.

Hey Steve. I’m so happy to hear of your backround and skill level. I shoot Sporter Rifle on the Freeport team and was wondering “who is this guy who consistantly shoot 290’s”?. Well, I got my answer when I saw your cool photo. I began shooting two years ago. A late start at 65. Catching your score has been my goal since last season. I found this great article through Googling your name. Thank you for your service soldier! God bless you brother! RANDY B.

Hi Randy! Thanks for the acknowledgement. Its ironic you mentioned Sporterifle. I’ve been involved in the program for 10 years now and I gotta tell you the job that Dave, Jerry, Terry and Lynn do for the Sporterifle program in New York State has been outstanding. A truly top-notch organization. And proud to be a part of it. And I’m sure you feel the same way. However after 35 years of competitive and military shooting, becoming a military sniper, and including a two year stint with the Army Marksmanship Unit (AMU), as well as competing in six different disciplines during those years, I’m calling it quits after this seasons Sporterifle. It just doesn’t seem like fun anymore and more of an inconvenience than an enjoyment. I think a lot can be contributed to the change in the shooting industry these last couple of years, just seems to me desperate times are upon us if your a hard-gun and competing in the shooting sports. The sanctioning bodies of the sport (I won’t mention specifically) as well as the ammo industry have a murky streak these days as compared to when I first started out in 85; now more of a money grab than a training tool for what they were intended to be. Sporterifle on the other hand maintains that high standard of a shining example of what the sport should be like. I hope Randy you achieve what you set out to in our Sporterifle League this season and in the future. Its been a pleasure competing with guys like yourself throughout, which was probably the best 10 years in the shooting sports for me.

God Bless you too, and who knows maybe someday we’ll connect for some Range time (Recreationally that is)……………………..

I have a friend who’s a devgru sniper, and while I’ve never talked specifics about just how good a shot he is, I have a hard time believing he wouldn’t give the best competition shooters a run for their money. You don’t become a devgru sniper unless you have as much natural talent as anyone, but I doubt most civilians have nearly as much practice: most people can’t afford to put tens of thousands of dollars down range. This also brings to light the fact that this comparison isn’t really equal bc it’s comparing the very best civilians with (barring a few exceptions) “very good” military snipers: the very best don’t exist outside of classified briefings. Also worth noting there’s a big difference between “can” and “will”: it would be nice to know people’s hit percentages when they talk about these really long shots. It’s hard to compare the relative skills of someone who can take a slightly longer shot with lower percentage and someone who shoots a little shorter but with much higher percentage. Also curious, when you said most of the competitive community could have made the shot to save captain Phillips with a handgun, did you mean including both boats’ motion, firing the moment ordered and not when you’re ready, or just a 100’ headshot? That final stipulation is key: being able to fire at the randomly moving target AT ANY TIME means you basically have to have 100% precision: if you can’t put basically the whole mag on target, you can’t really take THAT shot with a handgun. Think of it this way: to be ready for the green light, the sniper has to be tracking his target thinking “hit, hit, hit, hit, hit…” as if constantly firing, but only one “hit” coincides with the other snipers; if any of those would have missed, he would not have been able to maintain green status. In other words, if you couldn’t put the whole mag on target, you’re not getting the job.

Again, there are exceptions like Chris Kyle and perhaps yourself, but by and large I’d expect the “very best” military snipers to be in classified units like devgru, delta, sog… for all we know my friend regularly makes 2,000 yd shots, we’d never hear about it.

Your absolutely right Mike. First I just wanted to say I’m not degrading on how the SEAL shooters performed and the Captain Phillips situation. I should not have made that comment (comparison) about taking the shot with a handgun. Bad example on my part. Wished I could have taken that one back. Lots of variables involved in that engagement even though the distance was less than mid-range for shooting. So hard to judge a shooter in any capacity weather a military tactical engagement or as a civilian in a competitive platform. I’ve lived in both worlds and can tell you the only thing that exists between the two that I still truly believe in are the seven fundamentals of marksmanship. Yes the 7 fundamentals we all came to know in basic training and boot camp that aren’t really mentioned or taught much anymore these days especially in soldier BRM or initial marksmanship training. Military sniping and civilian competition those fundamentals are the common denominator to succeed at both. Also your assessment on the covert snipers and shadow warriors; a world most shooters never get to experience brings a whole new perspective on how good a skill set they have attained. I guess that is a question we’ll never know because of anonymity……………..

I totally agree with the article. It’s on point.

I am curious about your source regarding Jack Coughlin. He served in OIF 1 and he wrote a book about it. There’s no way his career spans back to Vietnam. That’s nearly 40 years apart.

This is an outstanding write-up. As a Ranger (pre-Gulf Wars) working in S3 for 1 1/2 years gave me the chance to help run the sniper training. At the time, I think we had kind of regressed since VietNam. However, we had two Rangers go to the Marine Sniper Course in Quantico, in the summer of ’83. I really think that was the turning point again for the Army in that someone above us valued the skills. We progressed slowly but not necessarily in great strides.

Along comes guys like Steve (I do not know him) who have really pushed the envelope of precision shooting. It’s come a long way and getting better. And, as he noted, the ability to meld the two disciplines together is what’s making our capabilities greater. Better equipment, especially cartridges, are finally coming on board.

Hi Todd –

Your 100% correct about the Army transitioning from the Marine Corps Scout Sniper Program into there own. It was a slow progression and in Feb 86 I attended which at the time was the Army’s Sniper (Counter-Sniper) School at Ft Campbell. That became the pre-curser to the highly prestigious Army Sniper Course at Ft Benning, which I also attended the following year 87 (the year the program was instituted). So absolutely your efforts early on; by getting guys involved into Sniper Training particularly from other branches probably was the spark that lit the flame that eventually afforded guys like myself and many others the opportunity to attend and become a proud graduate of the US Army Sniper Course /Ft Benning. I hope to meet you someday and shake your hand, share a beer and thank you. Rangers lead the way!!!! Steve Sciarabba

Hi good write up! I shoot competitive high power rifle. The BIG difference between “CMP” (Civilian Marksmanship Program) and sniper shooting is that we don’t use SCOPES on our rifles, rather we shoot 200, 300, & 600 yards with IRON SIGHTS only! Bid difference. I found this article because I’m getting ready to shoot at a local “sniper competition” during which for the first time ever I’ll be using optics during a match. Just wanted to clarify this!

Great article! Thank you for the enlightenment.